Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

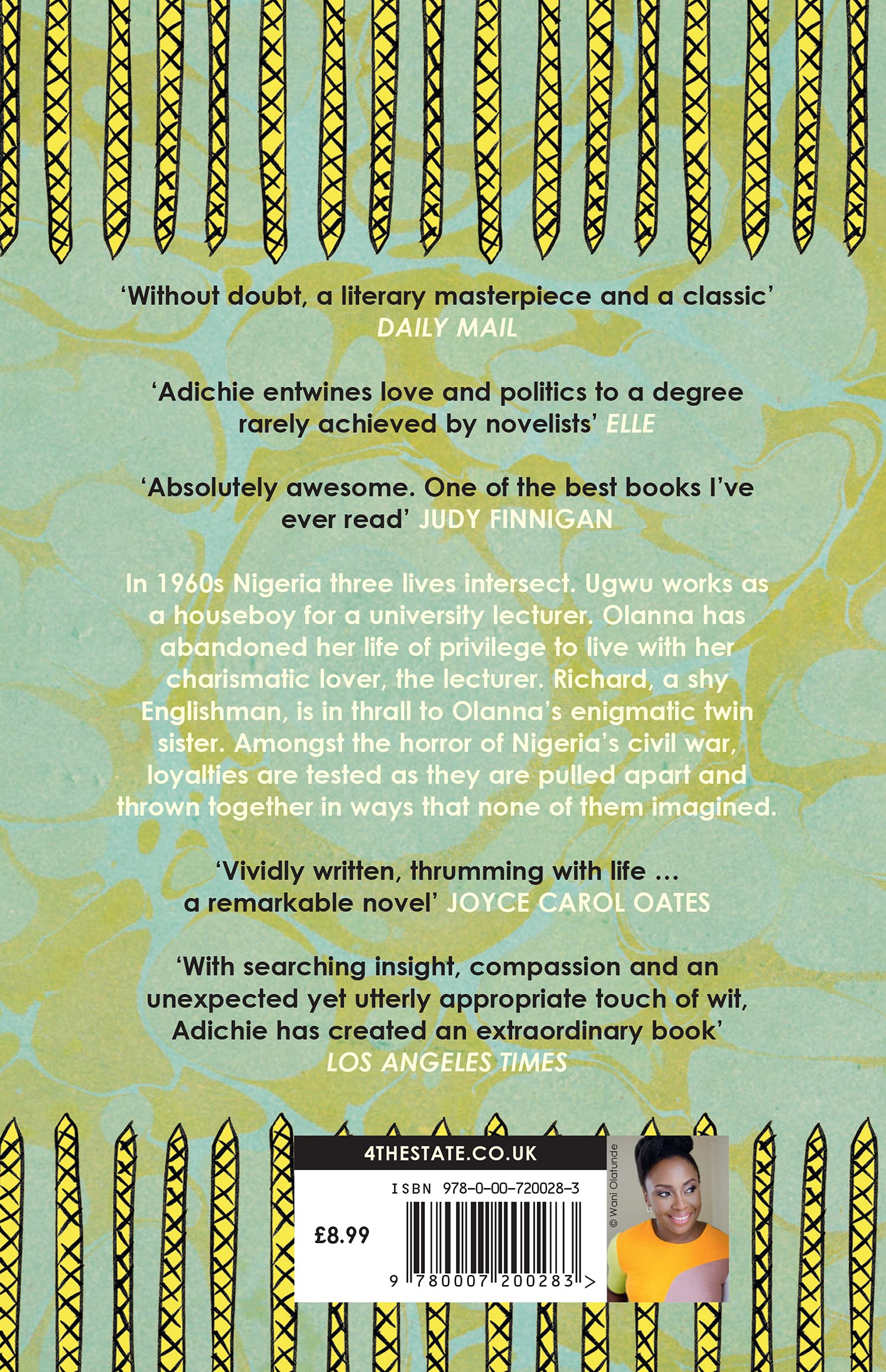

Buy Half of a Yellow Sun: The beautiful and literary, Women’s Prize-winning novel from global bestselling author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie by Ngozi Adichie, Chimamanda from desertcart's Fiction Books Store. Everyday low prices on a huge range of new releases and classic fiction. Review: Challenging and vivid story of the 1960s Nigerian-Biafran conflict - There has never been a better time to read Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Not only because it has recently been hailed as, 'A benchmark for excellence in fiction writing,' by the Baileys prize judges as they crowned it the ‘best of the best’ of the past decade’s winners. Not only if – like this reader – you were woefully ignorant of the Biafran war, its causes and consequences and your own government’s underhand behaviour throughout the period covered by the novel. Instead, read it because it really is an enlightening tale, far from being a dry history lesson, instead packed with vivid, memorable characters who it is difficult to step away from every evening when it becomes time to put down the book. Twin sisters Olanna and Kainene couldn’t be more different in their approach to life after graduation: Kainene dryly amused by her work in their father’s businesses while Olanna heads off to an unfashionable university in a outlying town to be with her boyfriend Odenigbo (who Kainene dismisses as ‘the revolutionary’). Events leading up to the outbreak of war between Nigeria and Biafra conspire to drive the sisters apart and it is not immediately clear that they will be able to resolve their differences amid the chaos. The stories are also narrated in part by Richard, Kainene’s British boyfriend, who is attempting to write a novel inspired by Igbo-Ukwu art and Ugwu, Odenigbo’s houseboy, whose adolescence, education and journey to maturity are interrupted by the fighting. This is a novel of bold ambition, not only in telling the stories of the war, but in dealing with the themes that engaged and challenged people through the 1960s. Olanna and Odenigbo are both academics, hosting colleagues and visitors at their home each night for lively, wide-ranging and drunken debates on the future of post-colonial Africa. Kainene and Olanna are both modern girls, keen to have careers and not be as dependent on their men as their mother perhaps is. Meanwhile fine distinctions abound – between wealthy Olanna (who after fleeing finds herself missing her tablecloths) and her aunt’s more down-to-earth family, the differences between the sophisticated city dwellers and the superstitions of village life, Richard’s attempts to distinguish himself from the other Westerners – which are often missed when the ill-informed speak of ‘Africa’ as one mass. Although set on a different continent, there is a lot here to inform about current events in Europe and the Middle East. Olanna and Odenigbo's failure to get out of harm's way, not anticipating the need to leave until literally the moment that they can hear shelling. And then, a form of internal exile as they move from one place to another, trying to remain in contact with friends and family who are similarly scattered, while facing starvation and diseases as deadly as the fighting. Ambitious in scope, but that ambition is realised in this wonderful, challenging and vivid story. Review: Worthy, but soapy and strangely unmoving… - When inter-ethnic warfare in Nigeria leads to the Igbo breaking away to form their own short-lived nation of Biafra, the five main characters in the book find themselves caught up in the slaughter and mass starvation that results. Olanna and Kainene are twins, the privileged daughters of a wealthy businessman, who have both returned to Nigeria after being educated in English universities. Olanna is in love with Odenigbo, an academic with strong nationalist and revolutionary leanings. Kainene falls for Richard, a white man who is failing to write the book he came to Nigeria to research, and whose main purpose is to personify white guilt. Then there’s Ugwu, servant to Odenigbo and Olanna – his purpose appears to be to show how devoted the servant class is to the privileged who sit around pontificating while their servants do all the work of cooking, cleaning and bringing up their children for them, while having to beg for an occasional day off to visit their families. This one took me nearly two months to read, largely because I found it almost completely flat in tone despite the human tragedy it describes. I learned a good deal about the background to the Biafran War, which happened when I was far too young to understand it but still registered with me and all my generation because of the horrific pictures of starving children that were shown on the news night after night for many months. I also learned a lot about the life of the privileged class in Nigeria – those with a conflicted relationship with their colonial past, adopting British education, the English language and the Christian religion while despising the colonisers who brought these things to their country. Adichie manages to be relatively even-handed – whenever she has one of her characters blame the British for all their woes, she tends to have another at least hint at the point that not all the atrocities Africans carry out against each other can be blamed on colonisation, since inter-ethnic hatreds and massacres long predated colonisation. In this case it is the Igbo who are presented as the persecuted – the same ethnic group as Chinua Achebe writes about in Things Fall Apart, a book which I feel has clearly influenced Achebe’s style. The attempt at a degree of even-handedness struck me in both, as did the method of telling the political story through the personal lives of a small group of characters. In both, that style left me rather disappointed since I am always more interested in the larger political picture than in the domestic arena, but that’s simply a subjective preference. I felt I learned far more about how the Biafrans lived – the food they ate, the way they cooked, the superstitions of the uneducated “bush people”, the marriage customs, etc. - than I did about why there was such historical animosity between the northern Nigerians and the Igbo, which personally would have interested me more. On an intellectual level, however, I feel it’s admirable that Adichie chose not to devote her book to filling in the ignorance of Westerners, but instead assumed her readership would have enough background knowledge – like Achebe’s, this is a tale told by an African primarily for Africans, and as such I preferred it hugely to Americanah, which I felt was another in the long string of books written by African and Asian ex-pats mainly to pander to the white-guilt virtue-signalling of the Western English-speaking world. Although I found all of the descriptions of life before and during the war interesting, the main problem of the book for me was that I didn’t care much about any of the characters. Just as I find annoying British books that concentrate on the woes of the privileged class, and especially on the hardships of writers, so I found it here too. Adichie is clearly writing about the class she inhabits – academics, politically-minded, wealthy enough to have servants – and I found her largely uncritical of her own class, and rather unintentionally demeaning towards the less privileged – the servants and the people without access to a British University education, many without even the right to basic schooling. Adichie is far more interested in romantic relationships than I am, and the bed-hopping of her main characters occasionally gave me the feeling I had drifted into an episode of Dallas or Dynasty by mistake. I was also a little taken aback, given Adichie’s reputation as a feminist icon, that it appeared that the men’s infidelities seemed to be more easily forgiven than the women’s, even by the women. (I don’t think she’s wrong in this – it just surprised me that she somehow didn’t seem to highlight it as an issue.) But what surprised me even more, and left a distinctly unpleasant taste, was when she appeared to be trying to excuse and forgive a character who participated in a gang-rape of a young girl during the war. I think she was perhaps suggesting that war coarsens us all and makes us behave out of character, and I’m sure that’s true. But it doesn’t make it forgivable, and this feminist says that women have to stop helping men to justify or excuse rape in war. There is no justification, and I was sorry that that particular character was clearly supposed to have at least as much of my sympathy as the girl he raped. So overall, a mixed reaction from me. I’m glad to have read it, I feel a learned a considerable amount about the culture of the privileged class of the Igbo and the short-lived Biafran nation, but I can’t in truth say I wholeheartedly enjoyed it.

| Best Sellers Rank | 3,763 in Books ( See Top 100 in Books ) 5 in Historical Military Fiction 85 in Political Fiction (Books) 136 in War Story Fiction |

| Customer reviews | 4.5 4.5 out of 5 stars (14,270) |

| Dimensions | 12.9 x 2.9 x 19.7 cm |

| Edition | 1st |

| ISBN-10 | 0007200285 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0007200283 |

| Item weight | 294 g |

| Language | English |

| Print length | 448 pages |

| Publication date | 16 Jan. 2025 |

| Publisher | Fourth Estate |

J**Y

Challenging and vivid story of the 1960s Nigerian-Biafran conflict

There has never been a better time to read Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Not only because it has recently been hailed as, 'A benchmark for excellence in fiction writing,' by the Baileys prize judges as they crowned it the ‘best of the best’ of the past decade’s winners. Not only if – like this reader – you were woefully ignorant of the Biafran war, its causes and consequences and your own government’s underhand behaviour throughout the period covered by the novel. Instead, read it because it really is an enlightening tale, far from being a dry history lesson, instead packed with vivid, memorable characters who it is difficult to step away from every evening when it becomes time to put down the book. Twin sisters Olanna and Kainene couldn’t be more different in their approach to life after graduation: Kainene dryly amused by her work in their father’s businesses while Olanna heads off to an unfashionable university in a outlying town to be with her boyfriend Odenigbo (who Kainene dismisses as ‘the revolutionary’). Events leading up to the outbreak of war between Nigeria and Biafra conspire to drive the sisters apart and it is not immediately clear that they will be able to resolve their differences amid the chaos. The stories are also narrated in part by Richard, Kainene’s British boyfriend, who is attempting to write a novel inspired by Igbo-Ukwu art and Ugwu, Odenigbo’s houseboy, whose adolescence, education and journey to maturity are interrupted by the fighting. This is a novel of bold ambition, not only in telling the stories of the war, but in dealing with the themes that engaged and challenged people through the 1960s. Olanna and Odenigbo are both academics, hosting colleagues and visitors at their home each night for lively, wide-ranging and drunken debates on the future of post-colonial Africa. Kainene and Olanna are both modern girls, keen to have careers and not be as dependent on their men as their mother perhaps is. Meanwhile fine distinctions abound – between wealthy Olanna (who after fleeing finds herself missing her tablecloths) and her aunt’s more down-to-earth family, the differences between the sophisticated city dwellers and the superstitions of village life, Richard’s attempts to distinguish himself from the other Westerners – which are often missed when the ill-informed speak of ‘Africa’ as one mass. Although set on a different continent, there is a lot here to inform about current events in Europe and the Middle East. Olanna and Odenigbo's failure to get out of harm's way, not anticipating the need to leave until literally the moment that they can hear shelling. And then, a form of internal exile as they move from one place to another, trying to remain in contact with friends and family who are similarly scattered, while facing starvation and diseases as deadly as the fighting. Ambitious in scope, but that ambition is realised in this wonderful, challenging and vivid story.

F**N

Worthy, but soapy and strangely unmoving…

When inter-ethnic warfare in Nigeria leads to the Igbo breaking away to form their own short-lived nation of Biafra, the five main characters in the book find themselves caught up in the slaughter and mass starvation that results. Olanna and Kainene are twins, the privileged daughters of a wealthy businessman, who have both returned to Nigeria after being educated in English universities. Olanna is in love with Odenigbo, an academic with strong nationalist and revolutionary leanings. Kainene falls for Richard, a white man who is failing to write the book he came to Nigeria to research, and whose main purpose is to personify white guilt. Then there’s Ugwu, servant to Odenigbo and Olanna – his purpose appears to be to show how devoted the servant class is to the privileged who sit around pontificating while their servants do all the work of cooking, cleaning and bringing up their children for them, while having to beg for an occasional day off to visit their families. This one took me nearly two months to read, largely because I found it almost completely flat in tone despite the human tragedy it describes. I learned a good deal about the background to the Biafran War, which happened when I was far too young to understand it but still registered with me and all my generation because of the horrific pictures of starving children that were shown on the news night after night for many months. I also learned a lot about the life of the privileged class in Nigeria – those with a conflicted relationship with their colonial past, adopting British education, the English language and the Christian religion while despising the colonisers who brought these things to their country. Adichie manages to be relatively even-handed – whenever she has one of her characters blame the British for all their woes, she tends to have another at least hint at the point that not all the atrocities Africans carry out against each other can be blamed on colonisation, since inter-ethnic hatreds and massacres long predated colonisation. In this case it is the Igbo who are presented as the persecuted – the same ethnic group as Chinua Achebe writes about in Things Fall Apart, a book which I feel has clearly influenced Achebe’s style. The attempt at a degree of even-handedness struck me in both, as did the method of telling the political story through the personal lives of a small group of characters. In both, that style left me rather disappointed since I am always more interested in the larger political picture than in the domestic arena, but that’s simply a subjective preference. I felt I learned far more about how the Biafrans lived – the food they ate, the way they cooked, the superstitions of the uneducated “bush people”, the marriage customs, etc. - than I did about why there was such historical animosity between the northern Nigerians and the Igbo, which personally would have interested me more. On an intellectual level, however, I feel it’s admirable that Adichie chose not to devote her book to filling in the ignorance of Westerners, but instead assumed her readership would have enough background knowledge – like Achebe’s, this is a tale told by an African primarily for Africans, and as such I preferred it hugely to Americanah, which I felt was another in the long string of books written by African and Asian ex-pats mainly to pander to the white-guilt virtue-signalling of the Western English-speaking world. Although I found all of the descriptions of life before and during the war interesting, the main problem of the book for me was that I didn’t care much about any of the characters. Just as I find annoying British books that concentrate on the woes of the privileged class, and especially on the hardships of writers, so I found it here too. Adichie is clearly writing about the class she inhabits – academics, politically-minded, wealthy enough to have servants – and I found her largely uncritical of her own class, and rather unintentionally demeaning towards the less privileged – the servants and the people without access to a British University education, many without even the right to basic schooling. Adichie is far more interested in romantic relationships than I am, and the bed-hopping of her main characters occasionally gave me the feeling I had drifted into an episode of Dallas or Dynasty by mistake. I was also a little taken aback, given Adichie’s reputation as a feminist icon, that it appeared that the men’s infidelities seemed to be more easily forgiven than the women’s, even by the women. (I don’t think she’s wrong in this – it just surprised me that she somehow didn’t seem to highlight it as an issue.) But what surprised me even more, and left a distinctly unpleasant taste, was when she appeared to be trying to excuse and forgive a character who participated in a gang-rape of a young girl during the war. I think she was perhaps suggesting that war coarsens us all and makes us behave out of character, and I’m sure that’s true. But it doesn’t make it forgivable, and this feminist says that women have to stop helping men to justify or excuse rape in war. There is no justification, and I was sorry that that particular character was clearly supposed to have at least as much of my sympathy as the girl he raped. So overall, a mixed reaction from me. I’m glad to have read it, I feel a learned a considerable amount about the culture of the privileged class of the Igbo and the short-lived Biafran nation, but I can’t in truth say I wholeheartedly enjoyed it.

J**K

This is a wonderful book about a time and a tragic war of which I knew almost nothing. I could not put it down. The story is deeply involving and the characters are achingly real. It is one of those books that make you feel as if you are watching the action unfold in an extraordinarily vivid way. I loved it. I thank the author for her wonderful gift to readers.

K**R

Amazing book, strong writing. How love, relationships between man and woman, siblings, parents and children are so universal. How war can bring up the worst and the best in people. If you remember Biafra this narrative will give it good context, very sad and beautiful at the same time

P**E

Une claque. Page turner saisissant autant que sensible et émouvant.

K**.

Absolutely delighted with the fact the novel with the correct cover was sent through following what may have been a misunderstanding. Thanks to the team! Yet to read the book, but happy to have it part of the bookshelf :)

L**L

Excelente escritora, prende sua atenção do começo ao fim. O livro é uma aula de história romanceada da tragédia que foi a independência da Biafra.

Trustpilot

3 weeks ago

1 month ago